Andalusia Wine Region

Share

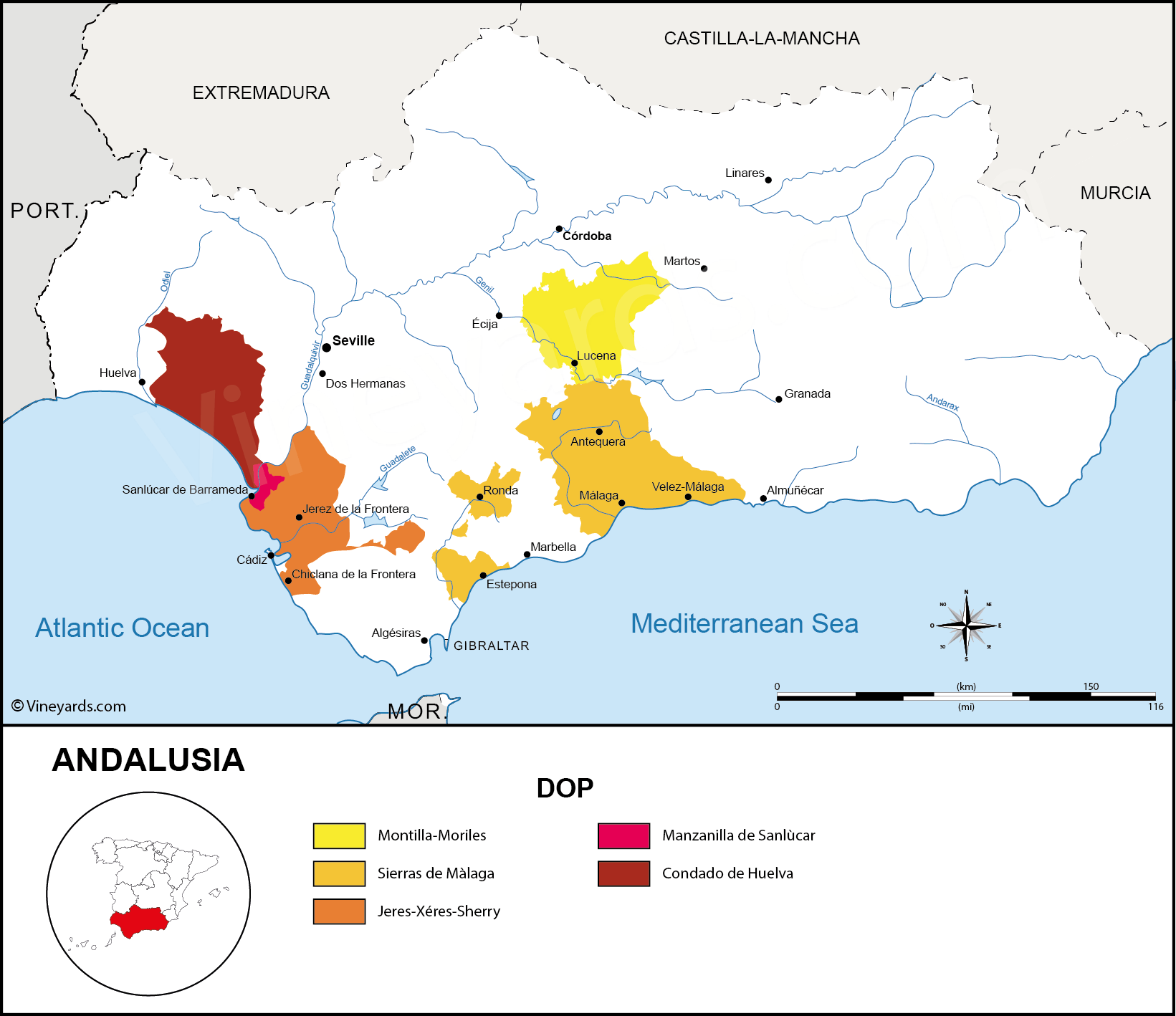

Andalusia wine region is the southernmost wine region of Spain and home to the world-famous fortified wine, Sherry. It has borders with Extremadura and Castilla-La Mancha to the north, Murcia to the east and Portugal to the west. From the southeast and southwest, it is surrounded by the Mediterranean sea and the Atlantic Ocean. The Mediterranean climate and mild average temperature make Andalusia wine region an ideal place for viticulture and winemaking.

The topography, geology and climate of Andalusia are all ideal for the cultivation of vines. The Mediterranean climate with all its different micro climates, the mild average temperatures (18ºC), the lack of frosts and hailstorms, and the long hours of sunshine, combine with the contrasting altitudes and systems of maturing to create wines of exceptional quality, with a wide variety of types and characteristics.

This focus on high quality production has remained right up until the present day and more than 70% of Andalusian vineyards are run under the auspices of one of the six Denominations of Origin which were set up and monitored by their respective Regulatory Councils: Condado de Huelva (1933), Jerez-Xérès-Sherry (1933), Málaga (1933), Manzanilla de Sanlúcar (1964), Montilla-Moriles (1985), and Sierras de Málaga (2001).

There are over 40.000 Hectares of vineyards in Andalusia.

HISTORY

During the Moorish period, the town known today as Jerez de la Frontera was called Sherish in Arabic, which both Sherry and Jerez are derived. The Moors conquered the region in 711 CE and introduced distillation, which led to the development of brandy and fortified wine.

In 1264 Alfonso X of Castile took back the city. From this point on, the production of sherry and its export throughout Europe increased significantly. Christopher Columbus brought sherry on his voyage to the New World and when Ferdinand Magellan prepared to sail around the world in 1519, he spent more on sherry than on weapons.

Sherry became very popular in Great Britain, especially after Francis Drake sacked Cadiz in 1587. At that time Cadiz was one of the most important Spanish seaports, and Spain was preparing an armada there to invade England. Among the spoils Drake brought back after destroying the fleet were 2,900 barrels of sherry that had been waiting to be loaded aboard Spanish ships. Because sherry was a major wine export to the United Kingdom, many English companies and styles developed. Many of the Jerez cellars were founded by British families.

By the end of the 16th century, sherry had a reputation in Europe as the world's finest wine. In 1894 the Jerez region was devastated by the insect phylloxera. Smaller producers were unable to fight the infestation and abandoned their vineyards entirely.

No other region of Spain has this mix of multicultural heritage. A unique way to discover this culture is by visiting the UNESCO world heritage sites such as the historic city centre with the Great Mosque in Córdoba, the Alhambra Palace in Granada, the Alcázar Palace and the Indies Archive in Seville, and the monumental sites of Úbeda and Baeza. Platters of fried fish ‘Pescaíto Frito’ from Cadiz and Malaga, cured ham of Huelva and Cordoba, olive oil, and other typical dishes such as Gazpacho and Salmorejo are a must-try here.

CLIMATE

The Jerez district has a predictable climate with almost 300 days of sun per year.

The rain mostly falls between October and May, averaging 600 mm.

The summer is dry and hot, with temperatures as high as 40 °C, but winds from the ocean bring moisture to the vineyards in the early morning and the clays in the soil retain water below the surface.

The year average temperature is approximately 18 °C.

GEOGRAPHY

- There are 3 types of soil in the Jerez district:

- Albariza: the lightest soil, almost white, which makes the Palomino vineyards in Cádiz look like a moonscape. It is approximately 40% chalk, the rest being a blend of clay and sand, and best for growing Palomino grapes. By law 40% of the grapes making up a sherry must come from albariza soil.

- Barros: a dark brown soil, 10% chalk with a high clay content. Barros are more fertile but also more difficult to work. This type of soil also has little moisture-retaining capacity due to a lower chalk content. It is prominent in low-lying valleys and at the foot of hills. This soil yields more grapes than albariza, but the quality is lower, so they result in a courser wine. Barros are not suitable for Fino wines.

- Arenas: a yellowish soil, 10% chalk but with a high sand content. Arenas are more common in coastal areas, especially in the area around Chipiona / Rota / El Puerto . They don’t hold water very well, so they are not suited for Palomino grapes. Instead they are mostly planted with Moscatel grapes – these grapes don’t need as much water and are happy on any type of old soil.

DO Jerez-Xérès-Sherry

Jerez-Xérès-Sherry is a DOP (1933) for a fortified wine made primarily from the Palomino grape, ranging from light versions similar to dry white wines, such as Manzanilla and Fino, to darker and heavier versions that have been allowed to oxidise as they age in barrel, such as Amontillado and Oloroso.

Most sherries are dry but sweet dessert wines are also made from Pedro Ximénez or Moscatel grapes, and are sometimes blended with Palomino-based sherries.

All wine labelled as "Sherry" must legally come from the Sherry Triangle, an area of 7000 hectares in the province of Cádiz between Jerez de la Frontera, Sanlúcar de Barrameda, and El Puerto de Santa María.

Annual sherry production is around 38 million litres.

WINEMAKING

The Palomino grapes are harvested in September and pressed lightly to extract the must.

The must is then fermented in stainless steel vats until the end of November, producing a dry white wine with 11–12% ABV.

After fermentation is complete, the base wines are fortified with grape spirit in order to increase their final alcohol content between 15.5% - 22%, depending on quality and final result intended.

Because the fortification takes place after fermentation, most sherries are initially dry (sugar content between 0-5g/L), with any sweetness being added later.

In contrast, port wine is fortified halfway through its fermentation, which stops the process so that not all of the sugar is turned into alcohol.

1) Sherry aged BIOLOGICALLY (under a layer of flor):

The fortified wine (up to 15.5% ABV) is stored in 500-litre casks made of North American oak, which is more porous than French or Spanish oak. The casks, or butts, are filled five-sixths full, leaving "the space of two fists" empty at the top to allow flor to develop on top of the wine.

Wines classified as suitable for aging as Fino and Manzanilla are fortified until they reach a total alcohol content of 15.5%.

As they age in a barrel, they develop a layer of flor—a yeast-like growth that helps protect the wine from excessive oxidation.

Fino is the driest and palest of the traditional varieties of Sherry. A sharp, delicate bouquet slightly reminiscent of almonds with a hint of fresh dough and wild herbs. Light, dry and delicate on the palate leaving a pleasant, fresh aftertaste of almonds. It is an ideal aperitif wine and goes well with all types of tapa, especially olives, nuts and Iberian cured ham.

Manzanilla is an especially light variety of Fino Sherry made around the port of Sanlúcar de Barrameda. Manzanilla Pasada is a Manzanilla that has undergone extended aging or has been partially oxidised, giving a richer, nuttier flavour. A sharp, delicate bouquet with predominant floral aromas reminiscent of chamomile, almonds and dough. Light acidity produces a pleasant sensation of freshness and a lingering, slightly bitter aftertaste. Manzanilla combines perfectly with fish and seafood, as well as with salted fish and cured meats.

Amontillado is a variety of Sherry that is first aged under flor and then exposed to oxygen, producing a sherry that is darker than a Fino but lighter than an Oloroso. Made from palomino grapes, this fusion of aging processes makes the Amontillado wines extraordinarily complex and intriguing. Its subtle, delicate bouquet has aromas of hazelnut and plants; reminiscent of aromatic herbs and dark tobacco. Light and smooth in the mouth with well-balanced acidity; both complex and evocative, giving way to a dry finish and lingering aftertaste with a hint of nuts and wood. Amontillado should be served at a temperature of between 12 and 14º C. It is an ideal wine to accompany soups and consommés, white meat, blue fish (tuna), wild mushrooms and semi-cured cheeses. Naturally dry, they are sometimes sold lightly to medium sweetened (5-45 g/l) but these can no longer be labelled as Amontillado.

2) Sherry aged OXIDATIVELY (in absence of flor):

The wines that are classified to undergo aging as oloroso are fortified to reach an alcohol content of at least 17%. They do not develop flor and so oxidise slightly as they age, giving them a darker colour.

Oloroso ('scented' in Spanish) is a variety of dry sherry aged oxidatively, producing a darker and richer wine. With alcohol levels between 17 and 22%, Olorosos are the most alcoholic sherries. Ranging from rich amber to deep mahogany in colour, the darker the wine the longer it has been aged. Warm, rounded aromas which are both complex and powerful. Predominantly nutty bouquet (walnuts), with toasted, vegetable and balsamic notes reminiscent of noble wood, golden tobacco and autumn leaves. There are noticeable spicy, animal tones suggestive of truffles and leather. Full flavoured and structured in the mouth. Powerful, well-rounded and full bodied. Smooth on the palate due to its glycerine content. The ideal temperature at which to serve an Oloroso is at between 12 and 14ºC. It combines perfectly with meat stews and casseroles; especially gelatinous meat such as bull's tail or cheeks. The perfect match for wild mushrooms and well cured cheeses.

Like Amontillado, naturally dry, they are often sold in sweetened versions called Cream sherry (115-140g/l, first made in the 1860s by blending different sherries, usually including Oloroso and Pedro Ximénez).

Palo Cortado is a variety of dry Sherry that is initially aged like an Amontillado, typically for 3 or 4 years, but which subsequently develops a character closer to an Oloroso. This either happens by accident when the flor dies, or commonly the flor is killed by fortification or filtration. Chestnut to mahogany in colour. A complex bouquet which harmonises the characteristic notes of Amontillados and Olorosos, citric notes reminiscent of bitter orange and lactic notes suggestive of fermented butter. It has a deep, rounded, ample palate with smooth, delicate aromatic notes appearing in the aftertaste, leading to delicious lingering finish. "Meditation wine," ideal to be slowly appreciated, It may accompany nuts, cured cheeses and, at the table, the more concentrated consommés, stews and gelatinous meats (bull's tail, cheeks...).

Jerez Dulce (Sweet Sherries > 160g/l) are made either by fermenting dried Pedro Ximénez (PX > 212g/l) or Moscatel grapes, which produces an intensely sweet dark brown or black wine, or by blending sweeter wines or grape must with a drier variety.

- Pedro Ximénez is obtained from the overly ripe grapes of the same name which are dried in the sun to obtain a must with an exceptionally high concentration of sugar. Its ageing process, which is exclusively oxidative, gives the wine a progressive aromatic concentration and greater complexity.

- A dark, ebony coloured wine with pronounced tearing and a thickness to the eye.

- In the nose its bouquet is extremely rich with predominantly sweet notes of dried fruits such as raisins, figs and dates, accompanied by the aromas of honey, grape syrup, jam and candied fruit, at the same time reminiscent of toasted coffee, dark chocolate, cocoa and liquorice.

- Velvety and syrupy in the mouth and yet with enough acidity to mitigate the extreme sweetness and warmth of the alcohol leading to a lingering, tasty finish.

- Pedro Ximénez should be served slightly chilled, at between 12 and 14ºC, though the younger wines may be served at lower temperatures.

- It is a dessert in itself (> 212g of sugar/L), though combining exceptionally well with desserts based on slightly bitter chocolate, with ice-creams and blue cheeses of great intensity, such as Cabrales or Roquefort.

- The Moscatel is one of the sherry grapes with pronounced fruity notes typical of this grape, produced either from fresh grape or sun dried, which has greater aromatic personality. The Moscatel vineyards are close to the beach in sandy soils with considerable maritime influence. Ageing is carried out exclusively with air contact.

- Ranging from chestnut to an intense mahogany in colour, with a pronounced density and tearing.

- The characteristic varietal notes of muscatel grapes stand out in the nose with the presence of the floral aromas of jasmine, orange blossom and honey suckle in addition to citric notes of lime and grapefruit and other hints of sweetness.

- It has a restrainedly sweet palate (> 160 g sugar/L) with predominant varietal and floral notes leading to a slightly dry, bitter finish.

- Moscatel makes the ideal combination for pastries and desserts which are not excessively sweet, based on fruit and ice-cream.

- Serve slightly chilled between 12 & 14° C in a white wine glass.

Solera Ageing System:

Wines from different years are aged and blended using a solera system before bottling, 2 years minimum, so that bottles of sherry will not usually carry a specific vintage year and can contain a small proportion of very old wine (VOS = 20 yo. VORS = 30 yo.)

Barrels in a solera are arranged in different groups or tiers, called criaderas or nurseries.

Each scale contains wine of the same age.

The oldest scale, confusingly called solera as well, holds the wine ready to be bottled.

When a fraction of the wine is extracted from the solera (this process is called the saca), it will be replaced with the same amount of wine from the first criadera, i.e. the one that is slightly younger and typically less complex.

This, in turn, will be filled up with wine from the second criadera and so on.

The last criadera, which holds the youngest wine, is topped up with the wine from the latest harvest, named sobretabla.

A saca (bottling of the old wine) and rocío (replenishing the casks) will usually take place several times a year, but the actual number may vary and specific figures are rarely disclosed.

In Jerez, a Fino solera will be resfreshed 2 to 4 times a year.

In Sanlúcar de Barrameda, due to the higher activity of the flor, a Manzanilla solera can easily have 4 to 6 sacas a year.

The pliego de condiciones (rules of the D.O.) states that you cannot sell more than 40% of the entire stock of a certain wine within the same year (which guarantees the required minimum age of all sherry wines).

In practice though there is an unwritten rule not to go over 1/3 in a single rocío (obviously less for Fino or Manzanilla).

For older wines there is usually 1 saca per year so for VOS or VORS sherry you need to prove that you keep X times the age statement in stock (e.g. 20x the amount for VOS wines).

WINES OF CORDOBA

Montilla-Moriles, located in the south of the Andalucian province of Córdoba, is one of the historical wine regions of Spain. The wine here has certain similarities with the Sherry of Jerez, but usually has suffered from the comparison. Montilla's dry finos have always been considered rougher than the equivalent Sherry, usually for lack of care in the wine-making process (though a good Montilla can be as fine as a good Sherry). Furthermore, in the past much of the region's production of Pedro Ximenez, the predominant grape in Montilla, was shipped to Jerez to sweeten their cream Sherries.

Now the dozen or so wineries in the 7,700 hectares Montilla-Moriles region are trying to make up for lost time and establish a name for themselves. They produce 24 millon litres of wine annually.

WINES OF MALAGA

Málaga province has long been famous for its sweet fortified wines, made from the Moscatel and Pedro Ximenez grape varieties. From the Phoenicians in the eighth century BC, the Greeks and Romans to the Moors and later the British, all enthusiastic drinkers of Málaga wines.

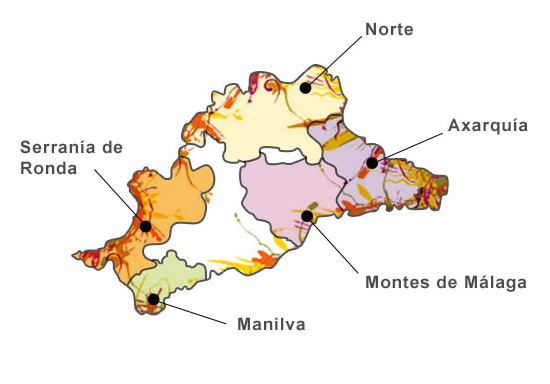

Malaga has 3 DOs (Denominaciones de Origen):

- DO Malaga (mostly sweet white wines)

- DO Sierra de Malaga (white, rose and red wines)

- DO Pasas de Malaga (raisins).

HUELVA WINES

Columbus set forth for his historical voyage from the port of Palos, in the western Andalusian province of Huelva. The navigator took with him his dreams of discovery. His crew, who came from Palos and neighbouring Moguer, took more practical things, such as dried tuna, legumes and, of course, a good supply of Huelva wine. Thus, Huelva's wines were the first Spanish wines to be exported to America (assuming, of course, that the sailors didn't drink it all along the way).

Huelva's wines are made with the Zalema, the indigenous white grape of the region. Traditionally it is used to make an amber-coloured oloroso-style fortified wine, Condado Viejo, an earthy, nutty, mouthfilling wine which goes well with the famous hams of the Huelva sierras. But living in the shadow of Jerez, this wine region seemed forever condemned to play second fiddle to its mighty neighbour. Many wineries went out of business, and those growers with good land switched to strawberries, now the major cash crop in the region.

Today, thanks to modern wine making technology, Huelva's wine trade is making a comeback, as wineries have started to produce unaged table whites from the Zalema grape. Well chilled, these wines - fresh, light, although a bit thin and not particularly flavourful - go very well with the local seafood. The best known brands are Castillo de Andrade (Bodegas Andrade) and Viña Odiel (Sovicosa).

The Condado de Huelva wine region covers an area of over 5,000 hectares and 40 bodegas which produce 28 millon litres of wine annually.

(Credit Photo : Ritmongo wineries)